"Plagiarize or Perish" at Harvard and MIT?

Trustless information will be a boon for journalists and academics, though it could put your favorite big media brand or university to rest.

Welcome, welcome, welcome!

This week’s edition is too long for email readers to display, so I recommend members click over to this post on our Substack to gain access to the whole edition.

Read the full post here: Immutabletype.substack.com

This one is a doozy at 10,000 words, so it’s a pretty deep dive best read on the website itself.

What’s covered

A raunchy joke

Alleged plagiarism by Claudine Gay

Bill Ackman’s Twitter/X threads

Alleged plagiarism by Oxman

Trust vs Trustless systems

Hard Reputations of an onchain world will save journalists

Let’s dive in!

PART ONE

Just One Goat

Let’s introduce the (newest) most important post-COVID cultural battle in America by starting with a very crude Irish pub joke, as told by Sir Paul McCartney. (Probs NSFW, fyi)

I’m slightly apologetic if the above joke and its language offend some readers, though it is a perfect joke for this conversation regarding reputation, so… crude language is the price we pay for clarity. I have chosen Sir Paul to deliver the punchline to help class up the content.

Goats All The Way Down

A cultural war has been brought to the campuses of Harvard and MIT in part by a prominent hedge fund manager named Bill Ackman. The conflict has escalated into the businesses of media company Business Insider, and its parent company, Axel Springer SE, which is majority-owned by the private equity giant KKR & Co.

“War” is typically a lazy description, and I’m using it here very aware we have multiple active military wars ongoing. Therefore, describing these events as a cultural war is done so intentionally to frame the depth of the fight between these parties and the resulting impact the outcome could have on citizens of the United States and elsewhere. The damage has already been significant, but we do not know if the final results will be a truce or a cultural transformation within America.

The parties involved appear intent on burning each other to the ground and are using accusations of plagiarism to inflict damage. “Plagiarism” is, of course, an unshakable label academics must avoid. In today's right-click-save world, stealing another's work is still the kiss of death for academic brands and their employees, and it’s becoming clear that a public accusation of plagiarism is an effective weapon in a cultural war between parties with deeply conflicted worldviews.

On the surface, some may find the subject of plagiarism to be an “elites” problem of little consequence for people outside the walls of the Ivy League system, not to mention a boring subject. Most people haven’t had to worry about plagiarism since their last term paper, and it doesn’t rise to the class of crime, so who cares if a bunch of elites are rolling in the mud over some failed citations and/or alleged intellectual theft?

What this perspective misses, however, is the weakness of our culture that has been exposed by this conflict; mainly, our reputations are soft, unverifiable, and can be exploited with little effort. Whereas trust between two parties has been necessary throughout history for agreements to be reached, it was a reputation that smoothed the path to agreements for parties when they did not know each other directly. Therefore, reputation systems are key features of civilization that allow people to more quickly coordinate together and conduct daily life. Without them, we would all become increasingly isolated into smaller and smaller social tribes of people who directly trust the members, and the isolation between tribes would fragment our commercial and social activities to only those with whom we have direct experience.

Reputation systems are tools that aid in creating harder reputations. We are all familiar with some common examples of these systems for individuals, including credit scores, background checks, and professional references. Consumers, likewise, engage with online product reviews that provide users with a 5-star rating scale on websites like Amazon, Yelp, Google Maps, etc. Uber even allows drivers to rate their passengers, which is genius. All experienced Uber passengers are highly aware that good reputations are hard to build and may require years of polite riding to establish. As with Sir Paul’s pub joke, however, a good reputation may not be any stronger than the most notable negative behavior or accusations of the reputation holder, and this is a soft area that is exploitable.

Plagiarism is the one goat of the publishing profession. One may not simply plagiarize once and be on with their work to teach students or inform the public. You can’t easily shake the label of being a plagiarist within the ethics of academic and journalistic professions, or among the public. Harvard and MIT leaders may not responsibly employ plagiarists and claim to hold their brand reputations to the highest standards, nor may a publisher support a journalist who lacks integrity in reporting or who steals the work of another.

And yet, with the stakes so high for reliable information, the reputation systems to quantify performance are quite soft for individual writers and academics when the public attempts to do their own research (#DYOR). There’s no 5-star rating system for information professionals, so it’s nearly impossible to verify which of these people is a reliable source of information. As a result, we are forced to rely on the reputations of the companies and brands that sponsor and monitor the work of their journalists and scholars.

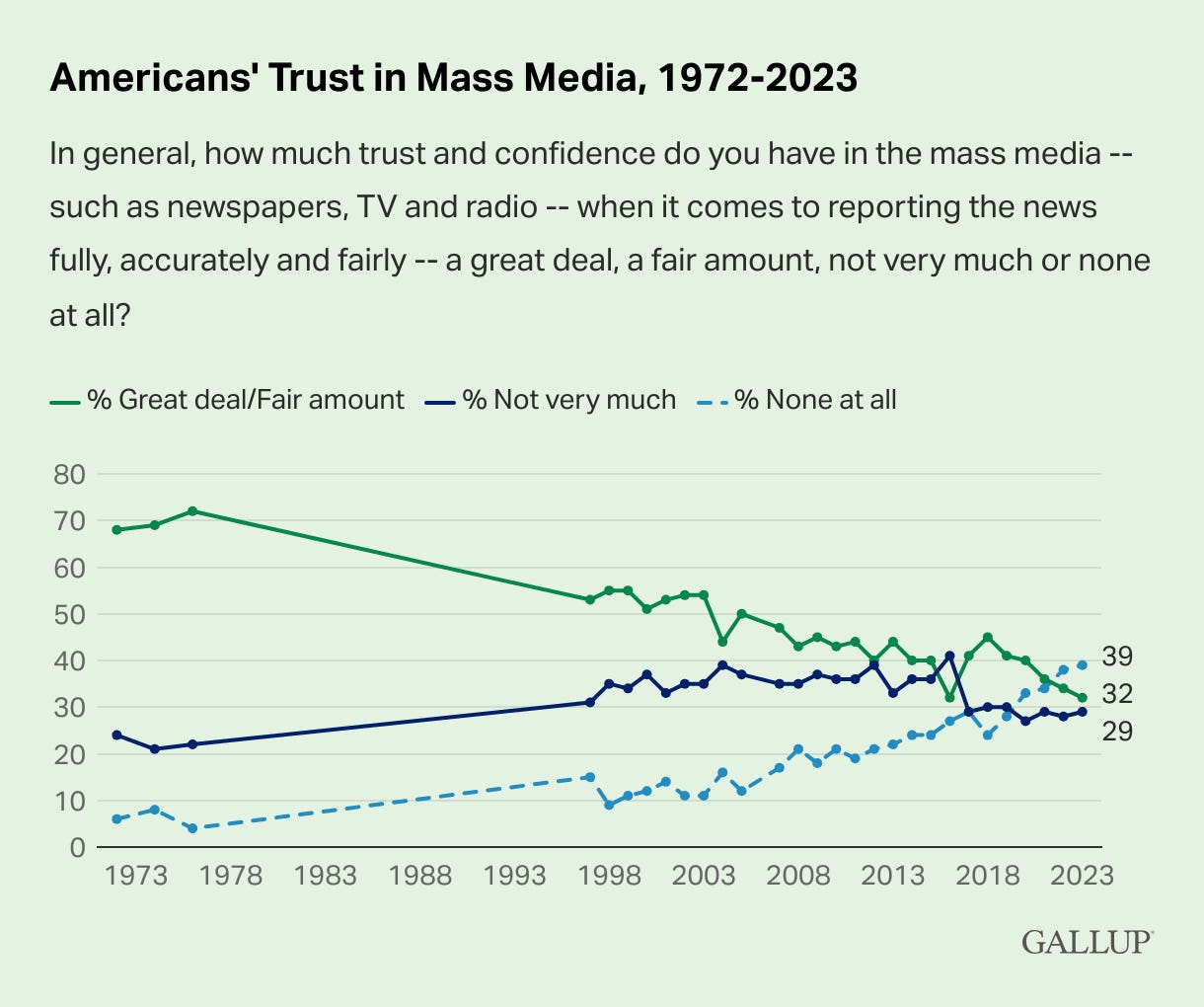

The reality, however, is that the public simply does not trust the media, and, also, the technology within the information landscape has become too advanced for traditional media and university models to keep pace. Advances in AI technology alone have further complicated the job of traditional media brands and audiences alike. The only choice information businesses have at this point is to wave a hand to distract the audience from its failings and to advise the audience to just trust us. It’s too naïve a request of course. The result is we don’t know who to believe and what actions to take when important conflicts open.

Ackman, Oxman, Gay, & The Media Complex

The culture war mentioned earlier is an incredible story from which to explore the challenges an audience experiences when it seeks to find the hard ground of truth beneath the headlines within the media. This example allows us to dive into reputations and our needs as a culture to develop harder reputations and trustless systems to continue to progress as a functional civilization.

As you’ll see from my Further Reading section at the end of this post, media consumers must spend considerable effort to unravel the interests of contributors within even a single story if we are to establish a fair context from which to form actionable opinions. The story about the story pulls in all levels of the players involved in such a controversial story, from the student protests on campus to the CEO of the parent company, from the journalists to the unions, and from funds flowing to university endowments to the funds of Henry Kravis and KKR’s ownership interests in the media properties; and, we even have characters from behind political operators to further spice up the pot. The gang is all here.

Here is the story headline and a link to the full article:

From Business Insider, January 4, 2024, 2:28 PM EST

Bill Ackman's celebrity academic wife Neri Oxman's dissertation is marred by plagiarism

This headline caught my attention for a few reasons, as I had been following the controversy between Bill Ackman and Harvard as part of my daily Twitter/X routine.

Ackman, in short, is a prominent Harvard alum who has been very vocal about his concerns regarding the lack of accountability by Claudine Gay, as well as the Harvard Corporation’s handling of her appointment as president and subsequent tenure. Gay ultimately resigned as Harvard president within six months of being hired for the job. The failings that led to her resignation were pretty stark, such as her tone-deaf answers to Congressional questions regarding Harvard’s policies for free speech and threatening language, and, separately, public allegations within the media that she had committed plagiarism within her academic publishing during her time at Harvard.

The first reason the story of Ackman’s wife being accused of plagiarism drew my attention is that it was a remarkable development of the broader story involving Gay, Ackman, Harvard, and MIT. The second reason is that Neri Oxman is a bit of a media star in academics and design, but the biggest reason is that the story immediately smelled like retaliation against Ackman. Oxman, despite being married to Ackman, is not directly involved in his conflict with Harvard. She was never part of the story.

My immediate objection to the story was that family is always off-limits. I believe every media outlet should know and honor this code to not attack family if not directly involved. In publishing the story, I surmised that Business Insider must have, either, crossed the line for a very good journalistic reason, or it was an active participant in this culture war, or, more likely, it was just shamelessly seeking clicks for its ad business by publishing a sensational story adjacent one in which a news cycle was ending.

Note that up until this headline about Oxman, I had simply believed the published reports about the Harvard scandal and Gay’s plagiarism, as I didn’t have a personal interest in digging any deeper to test the claims at the time. The headlines were enough for me to form the opinion that Gay was a plagiarist, which was not sufficient research on my part. I had simply read a headline and reacted rationally by believing what had been published was true. All I had read of the story were headlines, no articles, no photographs or snippets of the story, just the headlines that the president of Harvard was a plagiarist, and I believed it without too much thought. It didn’t spike on my radar that something else may have been going on.

This new headline regarding Oxman, however, immediately caused me to pause and pay attention to what was happening. I physically sat back in my chair and thought to myself, “What is going on here?” Individual academics from prestigious universities were being attacked in the media. Gay and Oxman each had built significant reputations, and someone seemed to be working to take each of them down with plagiarism accusations.

The problem for the audience is clear: we don’t know anything about the reputation of the journalists and researchers to assess their intent when we are presented with the story. We’re left to assume the brands have covered their bases and created an ethical process, but we simply cannot afford to grant that trust to the brands any longer. This uncertainty leaves the audience stuck between the known reputations of the academics, Gay and Oxman, and the unknown reputations of the journalists.

We can build a harder reputation system than this, so let’s do the work to begin.

Overview of Parties Involved:

It is helpful to outline a partial list of participants and their affiliations, as well as notable information about their CVs where possible. Where the political party is not included, I was unable to find a reference.

Note, this is not an investigative piece to see if we have a smoking gun within the newsroom or to identify who ordered the hits. My goal here is to outline how muddled it is for an individual to earnestly attempt to research the reliability of our information systems and land on an accurate opinion.

Claudine Gay, former president of Harvard. Princeton, Stanford, Harvard (PhD)

Harvard Corporation, responsible for appointing Gay

Elise Stefanick, Congresswoman, Republican, Harvard (AB)

Bill Ackman, CEO of Pershing Square Capital, Democrat, Harvard (BA, MBA), husband to Neri Oxman

Neri Oxman, Founder of OXMAN, Israeli, American, MIT (PhD), former MIT professor

Christopher Rufo, Activist, Republican, Georgetown (BS), Harvard Extension School (ALM)

Cofounded by Henry Blodget, Yale (BA)

Settled securities fraud charge with SEC. Banned from securities:

Sold Business Insider for $343mm to Axel Springer https://www.linkedin.com/in/henry-blodget-a541a3/recent-activity/all/

Barbara Peng, CEO, Business Insider, MIT (BS)

She has 2,713 followers on LinkedIn

She has not received any professional recommendations on her LinkedIn profile as of January 24, 2024

Issued this letter to address the Oxman controversy

Nicholas Carlson, Global Editor-in-Chief, Davidson College (BA)

He has nearly 40,000 followers on LinkedIn

He has received only one professional recommendation on his profile as of January 24, 2024

Katherine Long, Investigative Reporter, Brown University (BA), Columbia University (MS)

Jack Newsham, Senior Reporter, Yale (BA)

Jake Swearingen, Deputy Editor, University of Arkansas (BA)

https://www.linkedin.com/in/jake-swearingen-15aa682/

No recommendations received; two given; 1,498 connections

John Cook, Executive Editor for News, University of Wisconsin-Madison (BA)

https://www.linkedin.com/in/john-cook-97b76417/

Seems strange he only has 143 connections. Not verified identity on LI.

Recently locked his X.com account after staff layoffs and a lawsuit by Ackman

Wrongly associated with the Hulk Hogan lawsuit while he was Executive Editor of Gawker in 2015

Axel Springer SE owns Business Insider, Inc., and itself is majority-owned by the PE firm of KKR

German media giant with over 16,000 employees

Claims of CIA funding on its Wikipedia page

Claims of conducting “a decades-long record of bending journalistic ethics for right-wing causes” per its Wikipedia page

Published corporate value #2: We support the Jewish people and the right of existence of the State of Israel.

Axel Springer management

Mathais Dopfner, CEO, Axel Springer SE

Owns 22% of Axel Spring SE, 15% of which was gifted by the widow of Axel Springer, Friede Springer, and holds 44% voting rights of the firm

Led acquisition of Business Insider and Politico

Accused and found guilty of “scientific misconduct” and plagiarism of his dissertation at the Goethe University of Frankfurt

Conservative and widely connected

KKR

Owns and controls 48.5% of Axel Springer SE after taking it private

Union influences are present but not well-documented

Sequence and Summary of Events:

The starting point for this story really begins October 7, 2023.

October 7, 2023: Hamas executed violent attacks upon Israel civilians

October 8, 2023: The Harvard Palestine Solidarity Groups signed by 34 signatories and published publicly along with a statement announcing in part, “hold the Israel regime entirely responsible for all unfolding violence.”

Names of the 34 signatories were withdrawn by Tuesday, October 10 for safety reasons

October 9, 2023, at 12:40 PM: Lawrence Summers, former president of Harvard, issues statements on X.com. His thread has received nearly 20mm views through January 2024.

In nearly 50 years of @Harvard affiliation, I have never been as disillusioned and alienated as I am today. - Lawrence H. Summers

October 9, 2023: Harvard issues A Statement from Harvard University Leadership

October 10, 2023, 1:00 PM: Ackman posts to X.com that the student member names should be made public if they indeed support the co-signed letter. It has received 24.4mm views to date, January 2024.

October 10, 2023, no timestamp: Harvard issues A Statement from President Claudine Gay

October 12, 2023, 1:04 PM: nine of the signatory groups retracted their signature

October 12, 2023, no timestamp: a video titled, A Message from President Claudine Gay is published on the Harvard website.

October 13, 2023: Elise Stefanik, Republican New York Congresswoman, calls on Gay to resign via a post on X.com sharing Gay’s video.

October 24, 2023: The New York Post contacts Harvard for comment regarding anonymous information it had received claiming instances of plagiarism by Gay.

October 27, 2023: The New York Post receives a defamation letter from Harvard outside council.

November 4, 2023: Ackman posts on X.com his letter to Gay regarding his assessment of her performance in addressing anti-Semitism on campus.

December 3, 2023: Ackman posts on X.com his follow-up letter to Gay regarding his insights into DEI practices of Harvard and notes, “I hope that having to face the Congress on Tuesday will be a wake-up call for you.”

December 5, 2023: President Gay testified before Congress, along with the presidents of MIT and the University of Pennsylvania. The hearing was titled, “Holding Campus Leaders Accountable and Confronting Antisemitism.”

December 5, 2023, 6:25 PM: Ackman calls on the three university presidents to “resign in disgrace.” The post had received 107 million views as of January 2024.

December 10, 2023: Christopher Rufo, a conservative activist, published a post on his Substack titled, “Is Claudine Gay a Plagiarist?”

His X.com post of the same day has received nearly 40 million views to date.

December 11, 2023: Reporter Aaron Sibarium published his story in the Washing Free Beacon directly accusing Claudine Gay of plagiarism.

December 12, 2023: The Harvard Corporation issues a statement of continued support of Gay as the president of Harvard.

December 17, 2023: Carol M. Swain, one of the scholars who was cited as having been plagiarized published an opinion article on WSJ.com. Swain objected to the notion that the examples of plagiarism by Gay were insignificant, writing, “The damage to me extends beyond the two instances of plagiarism identified by researchers Christopher Rufo and Christopher Brunet.”

December 20, 2023: The House Committee on Education issues a letter to The Harvard Corporation notifying it of its action to begin a review of the allegations of plagiarism by Gay.

January 2, 2024: Gay announces resignation as president of Harvard.

January 2, 2024: Ackman posts, “Et tu, Sally?” on X.com in reference to Sally Kornbluth, president of MIT, and the remaining sitting president who testified before Congress on December 5.

January 4, 2024, 2:28 PM: Katherine Long and Jack Newsham of Business Insider published a story accusing Ackman’s wife and former MIT professor, Neri Oxman, of plagiarism.

January 4, 2024, 2:35 PM: Oxman posts her answer to the story on X.com

January 4, 2024, 2:48 PM: Ackman shares his wife’s post and provides additional context on X.com

January 4, 2024, 3:19 PM: Ackman re-shared a post on X.com from @retselfL about concerns about a history of anti-Semitism mismanagement by MIT president, Sally Kornbluth, while she served as provost of Duke University.

January 5, 2024, 6:59 PM: Katherine Long, the BI reporter, posts to X.com and tags Ackman, “I sent these receipts, and dozens more, to @BillAckman earlier today, hopping they would help him do the research he said he had no time to do before blasting us here.”

The misspelling of “hoping” is hers and left inline

Ackman replied to her within the thread of her post with details of timestamps describing less than two hours to respond, as well as refuting that the journalist, Long, and he had ever spoken.

January 6, 2024, 7:30 PM: Ackman posts to X.com a very significant and detailed two-part account of timelines and descriptions of his and Oxman’s engagement with Business Insider reporters and management.

January 7, 2024, 8:15 AM: Ackman posts to X.com a follow-up from the January 6th post asserting the BI sources came from within MIT.

Ackman wrote, “And to be clear, we do not know for a certainty that

@MIT is behind this, but we have good reason to believe this to be true.”

January 7, 2024, 4:08 PM: Ben Mullin, a New York Times media reporter, posted on X.com that Axel Springer is going to take a couple of days to “review the processes” in relation to the Oxman story.

Quotes Axel Springer, “The facts of the reports have not been disputed.”

A screenshot of his notes reads: Our media brands operate independently

January 7, 2024, 5:41 PM: Mullin shares screenshots from an internal email by Nicholas Carlson, BI Global Editor-in-Chief, on X.com. The email includes a quote from the email by Carlson, “The facts of the stories have not been disputed by Oxman or her husband Bill Ackman.”

January 7, 2024, before 6:01 PM - (Unable to verify timestamp): Nicholas Carlson, BI Global Editor-in-Chief, shared the post by @benmulli of the screenshots of his internal email quoting…himself…

January 7, 2024, 7:03 PM, Max Tani of Semafor.com reported that Axel Spring SE, the German parent company of Business Insider, had decided to “review the process around these stories.”

January 8, 2024: 6:40 PM: Mullin posts the response from the Insider Union and The NewsGuild of New York to the Axel Springer review of the internal process at BI

January 9, 2024: The @InsiderUnion issues a press release dated January 8th in objection to Axel Springer’s statement to review the “process” for their journalists.

The PR announcement containing the objection is dated January 8 but is posted on January 9th at 11:01 AM to X.com on the union’s account

The date of the press release on their website shows 1/09/2024

January 9, 2024, 7:46 AM: Ackman posts his objections on X.com regarding the quote from Carlson and Axel Springer that the facts were not being disputed.

Ackman wrote, “Mr. Carlson is lying or he has been misled by others.”

He continued at length of how he and Oxman had indeed disputed the facts.

Ackman publicly provides significant notes of the conversations in support of his position.

Elon Musk posts to Ackman’s thread, “I recommend a lawsuit.”

January 9, 2024, 4:18 PM: Ackman posts on X.com in part “MIT's academic integrity handbook did not require citation or even mention Wikipedia until 2013, four years after Neri wrote her dissertation and used Wikipedia for the definitions of 15 words”

He poses a question to private equity and finance communities: What is the net worth of Axel Springer?

January 10, 2024, 8:10 PM: Ackman posts a full timeline and names names of the conversations. This is a significant post with many important timeline details.

Of major significance to support his defamation claims are the disputes of facts directly with Business Insider and Axel Springer’s top leadership.

January 14, 2024, 10:06 AM: Barbara Peng, Business Insider CEO, posts a letter on Business Insider and affirms the position, writing, “There was no unfair bias or personal, political, and/or religious motivation in the pursuit of the stories.” and continues, “The stories are accurate and the facts well documented.”

Peng is a graduate of MIT

The letter is shared by Mullin, Tani, and widely by BI staff on X.com

The BI website landing page displaying this letter includes ad placements directly generating revenue from traffic visiting the letter to read its contents

January 14, 2024: no timestamp available: A reporter named Sam Jones of the Financial Times published a story headlined, “Internal review backs Business Insider reporting of Oxman plagiarism claims”

Sam Jones has 11 followers on LinkedIn and includes the message “I don’t use LinkedIn”.

He has published his X.com handle on his FT bio page.

The X.com handle is for an account that doesn’t exist @samgadjones.

He informs users on his Muckrack bio “I don't use this anymore.”

January 14, 2024, 8:51 PM: Ackman shares the FT article as a post to X.com and comments, “Now that Business Insider and Axel Springer have tripled down on their false claims and defamation, they have amplified their exposure, and for that I am grateful.” He continues, “We will respond in a formal complaint which will take a few weeks to prepare.”

At 9:21 PM he clarifies further with a reply to his above post. “By complaint I mean lawsuit, to be clear.”

January 25, 2024, 8:15 AM: Max Tani posts to X.com an internal email from Business Insider CEO, Barbara Peng to the company employees notice of a layoff of 8% of BI staff.

January 25, 8:39 PM: Ackman posts on X.com an update regarding the layoffs, noting, “It appears that Business Insider has not yet terminated Nicholas Carlson, John Cook, or Katherine Long.”

As well as sharing a screenshot of John Cook’s X.com account having changed status to protected in which his posting history is hidden from the public.

Cook is the BI Executive Editor for News and oversaw the story. @johnjcook

Neri, or Ne’er do-Well?

I think a fair question to ask at this point is, “Why did we just review all that information?”

Yes, I get it, this seems a bit crazy in hindsight, BUT this is exactly the work I needed to complete to figure out who to trust and which reputation deserved to be downgraded. It’s a demonstration of real-life experiences within the media.

All this effort was expended only for unraveling the level of belief I should assign to a single news story accusation that Neri Oxman is a plagiarist.

I won’t hold the suspense, because my conclusion is not the discussion I want to have. No, after all this research and backstory gathering, I do not believe Neri Oxman is a plagiarist. It was a LOT of work to feel comfortable with this conclusion, but that was part of the exercise, doing the work.

I finally landed upon this decision because of what I did NOT find, which was that none of the people Oxman allegedly plagiarized came out strongly and objected to her use of their work or labeled her as a plagiarist. The supposed plagiarized did not feel strongly enough that she had plagiarized their work to post any opinion pieces in major newspaper publications, nor did MIT issue any opinion that I could find. The accusations began and ended with Business Insider and its staff.

Plagiarism is about intent, and while both Gay and Oxman were accused of sloppy writing and failing to use proper punctuation when citing sources, only Gay had a source come out publicly and chide her. Carol M. Swain published an Opinion article on WSJ.com, and this paragraph solidified my conclusion of the two accused:

When scholars aren’t cited adequately or their work is ignored, it harms them because academic stature is determined by how often other researchers cite your work. Ms. Gay had no problem riding on the coattails of people whose work she used without proper attribution. Many of those whose work she pilfered aren’t as incensed as I am. They are elites who have benefited from a system that protects its own. - Carol M. Swain

The reputation of Swain as the source is what gives her so much weight in my opinion, because I trust her to be aggrieved as one of the few who have the right to offer an opinion of the intent of Gay. Oxman had no such lament from her sources, and that was a strong signal for me. Nobody felt their reputations were damaged by Oxman’s use of their work.

My willingness to risk some small part of my reputation is what gives weight to my opinion that Oxman is not a plagiarist. It’s the collateral I have to argue on Oxman’s behalf, and it’s the opinion I’ll hold whenever I encounter her work in the future.

By contributing the little weight I have to the scale of public deliberation, the soft reputation system tips very slightly more toward Oxman’s favor and away from MIT, Business Insider, Axel Springer SE, KKR, and all the named individuals within each of these organizations. My opinion is supported by ample references to important articles and posts regarding both Gay and Oxman, as well as a good summary of the individuals involved on the media side of the business. Were this process automated for the audience for all published work, then these stories would each hold more weight at the time of publication. This would certainly be a technical challenge to accomplish among traditional media today.

But, who am I, and does my opinion add enough weight to the scale to help, meaning is my opinion worth all this effort to research, summarize, format, and share publicly? My opinion is not even networked into the conversation with the mainstream media, and this work here will be seen by relatively few readers outside my direct network. So why do it?

The answer is, in part, that we really shouldn’t have to go through all this work to assemble an informed opinion and share it with a few thousand people in a personal network. I did the work as an example to illustrate the challenges we all face in determining truth when it becomes necessary to evaluate the reputations of institutions, individuals, and our representatives within the media, specifically the journalists.

I did this work to lead us into discussions to outline solutions that establish hard reputations that work at scale. Hard systems will free audiences from uncertainty, while also freeing individual journalists and academics from traditional information intermediary employment models.

We’ll have to build it the hard way, FYI. Keep scrolling.

PART TWO

Hardhats & Blocks

With the groundwork set to outline the headwinds for individuals within the legacy media system, we are now able to build a system to solve the needs of this lagging industry.

I will use some examples from the above to discuss the new onchain methods below. I recommend familiarizing yourself with Part One above if only to recognize the names of individuals below.

My opinion is we need to build in parallel with the existing media complex and migrate behavior to the new information network experience. There will be many opportunities to work within the legacy model, but the majority of those engagements will simply embed or fork the work we build. This is good news and is welcomed.

The media landscape is now a construction zone.

Trustless Systems > Trust

What’s better than trusting relationships? Trustless relationships!

The word “trustless” has taken me some time to fully internalize personally, but a good way to think about it is that a trustless system is built so it cannot lie, or at least, it can’t behave outside the verifiable public code. It is free from trust, because a trustless system is unable to be trusted or mistrusted.

Can’t Lie is the easiest working concept to remember when thinking about a system being trustless.

“Trust Me” Systems

A system with an intermediary requires some level of trust to govern transactions between multiple parties, whether it’s peer-to-peer, one-to-many, or many-to-many.

No two words, however, raise more red flags than a person who says, “Trust me.” Why would that be? Because saying, “Trust me” announces that the potential to lie exists, so the party seeking trust must explicitly request it. A request to “Trust me” means the party requesting it does not have enough evidence available to make a convincing case that the agreement will be completed. Something could always go wrong after the handshake.

Despite that setup, trust me systems are what we are accustomed to in daily life. Banks, governments, media companies, all our subscription services, payment cards, car warranties, insurance companies, everything relies on trust to deliver upon an agreement. We all know this trust could be violated in some ways, but it’s the system we have, so we accept the likelihood of some loss of value by agreeing to accept the terms of service from the other party.

Media brands and academic institutions are information intermediaries that operate trust me systems to establish a consensus of what is true or accurate about information. Their business is to generate revenue by providing information to an audience that meets their internal standards for truth and accuracy. The consensus for what is true and accurate is reached internally and then published to an audience as information that has met the information intermediary’s standards. Our trust is put in the hands of the intermediary because we are not present to observe the execution of their policies. There is no mechanism to confirm they have done as promised, and there is no public dashboard to display their historical performance and track record.

Axel Springer SE, for example, conducted an internal review of the processes used by Business Insider to develop and publish the Oxman story. The standards of the review were not made available to the public, nor were the methods of evaluation. The audience was left only with a choice to trust or distrust a published report from Sam Jones of the Financial Times that Axel Springer SE was satisfied with its findings. The article by Jones was very thin for such a big story about media practices, and Jones himself has a very weak online reputation to be entrusted with such a story, yet it’s all we have. We have a headline, effectively, which waves a hand and assures that everything is fine. In short, we’re asked to “trust me” as an audience of the Financial Times.

Trust is the key for these businesses when operating “trust me” systems for consensus about what information is true and accurate. The job of an information intermediary is to gather, organize, format, and distribute uniquely actionable information. Trust makes that work actionable. If no trust, then no action. Action is the only value output for which the audience is willing to pay a fee. If no trust, no action, and no fees paid…

This seems so obvious, but the lack of public trust in media brands is precisely the problem we have today. The result of this lack of trust is an industry in crisis with widespread media company layoffs and closures. Information that is not both unique AND actionable is not valuable to any audience, so we churn from buying their services as the audience. The media brands and agents that fail to create actionable information not only destroy investor value, but ultimately damage the entire industry by operating at all.

This void in trust has spurred the development of new tools and services from outside the academic and media systems. The goal of the tools is to help improve the audience’s understanding of the accuracy of information within trust me systems, such as plagiarism detection technology and media rating services. Each product type is effectively a monitoring solution, so the product really lacks sufficient features to increase information clarity for consumer audiences at scale in real time. The technology just doesn’t have the juice to keep up with such a soft system.

Plagiarism software, for example, has been used by educational institutions for years with the purpose being to prevent students and faculty from passing off plagiarized works as their own. Recently, however, activist researchers have turned the plagiarism software upon academic work published before the adoption of the software by educational institutions. The result is the activists have identified significant failures of the trust me system of peer review at Harvard, and one must believe this type of research will turn up similar damaging results across most academic institutions once AI-enabled tools are tasked with the job. Regardless of the scope of the peer review failures that come to light, the minimum finding will be that trusting an intermediary to deliver accurate information will not be entirely reliable. It’s time to externalize that job to a network and stop trusting intermediaries to behave properly.

Media monitoring services, for their part, do address bias by the media brands, but the results don’t reach the audience at the time when the audience needs that information, which is at the point of engagement. While these media monitoring services do appear to provide relevant and accurate results, the ratings only address the historical performance of the brands, rather than the individual stories published under the banner of the brand. Additionally, the agents of the intermediaries (journalists & editorial management) are not ranked or indexed, so the range of bias of any individual story is unknown at any time. Monitoring services do provide value, but their impact is too low to be powerful.

We can solve these blind spots with trustless systems.

“Trustless” Systems

A trustless system does not require an intermediary to validate transactions between peers. It can only execute the public code.

Blockchains are trustless systems, for example, where the parties that agree to a transaction need not know each other directly, nor rely on the reputation of the other peer’s intermediary to have enough confidence to complete a transaction. Unlike a trust me system, an effective trustless system cannot lie.

As noted, Business Insider, MIT, and Harvard are information intermediaries because they are the entities that have established the policies that govern their agents as the layer of promises between the raw information source and the audience. The act of governing the performance of its agents is conducted by officers and directors of the intermediary away from public view. Again, we must trust the intermediary to not lie when reporting its conclusions.

A trustless system eliminates the need for the services of information intermediaries because trust is no longer required by the audience. Trust is only a criterion when the reputation of an intermediary is necessary to assure the audience that information has been gathered, organized, formatted, and distributed in a manner that contributes uniquely actionable information to the audience experience.

The trustless system, however, does the job of assuring compliance within governance criteria, so agents can operate freely between the information source and the audience as a commentator of subject matter. All the jobs previously completed by the information intermediary are executed publicly according to coded criteria that are verifiable and immutable. The journalists and the academics become the information stewards, and the code validates the criteria that have been met on behalf of the networked audience.

In a trustless system, “code is law” therefore any behaviors outside the encoded criteria may NOT pass through the network, regardless of the reputation of the actor. This is a hard system to replace our existing soft systems. The code is incorruptible governance, so we may have confidence as the audience that the information we access has met the publicly verifiable criteria of the trustless system. The audience doesn’t need to hope the intermediary honors journalistic integrity as part of their obligation to a professional guild, or question if such a commitment is little more than a magic cloak to ward off inquiry when the business reviews the work of its agents. We will simply know the code executed as designed.

One of the key features of an effective trustless system is that it is immutable. The transactions are incapable of being corrupted, bribed, or attacked successfully, and this is quite appealing when we’re dealing with information integrity. History, for example, may not be rewritten to serve the needs of those who would like to change it. In a trustless system, what is stored onchain may only be appended to previously published information. Histories stored onchain may not be augmented or entirely wiped away at the command of any new power, as the code will not allow that action. We won’t lose Alexandria again; cultures won’t be obliterated; and, histories won’t be dictated tops down.

The Reputations We Deserve

Authors, scholars, and journalists are mostly employees of the trust me system, and their soft reputations are formed from their ability to navigate that type of political environment. Breaking free from that soft system will be a financial boon for the most effective information professionals because the market will reward the best and most valuable work, not the person most adept at navigating corporate politics.

For these information professionals to break free, however, we need an onchain hard reputation system free from trust and the influence of intermediaries. Such a system could be configured with five key factors to help establish the credentials of each individual:

Verifiable identity

Network value

Productive history

Expertise & knowledge (Read-to-earn)

Opinions and Bias

Let’s go over each briefly, as it’s easy to see how this comes together to form a much-improved system with a bit overview.

1. Verifiable identity

The individual must be verifiable as THE human they are representing within a trustless system. This is becoming incredibly difficult today. Anyone who has spent much time on social media understands the risk of bots and parody accounts spreading information and misinformation.

To be clear, we do not need to dox the individual to verify their identity. Cryptography provides the ability for an account identity to be verified AND private, so a pseudonymous writer may develop and publish information without fear of retribution. Why is this good? Because bad guys exist, and exposing bad guys comes with some level of risk. If we are able to verify identity but protect the source of information, the public will gain access to more abundant accurate information that is uniquely actionable from verified anonymous sources.

The most famous example of a pseudonymous identity in blockchain culture is of course, Satoshi Nakamoto. His/her government identity is unknown, but his/her identity is verifiable within a trustless system. Were he/she to write a new post today, the only verification of identity necessary would be for him/her to transfer a small fraction of Bitcoin from Satorhi’s historical Bitcoin address to a new address. Doing so would prove the verifiable identity of the pseudonymous writer and allow us to have confidence the information source was Satoshi Nakamoto.

Within the Oxman story, we have at least one instance of identity verification that fails to satisfy research. Sam Jones of the Financial Times is a difficult contributor to verify. He is the writer credited with breaking a pretty big piece of the story about the internal investigation by Axel Springer SE of Business Insider’s processes, yet there is very little information available online to verify his identity. Indeed, from most of his social media and public bios, he’s a non-participant in common platforms that would typically verify identity. I find this odd, and it creates distrust in the information he has published. His identity is very weak within X.com, Linkedin.com, Muckrack.com, as is his bio on the Financial Times’ website, which creates doubt about the credibility of his report that Axel Springer SE closed its investigation without concerns. Who is Sam Jones? We just don’t know. He has very little in the way of online reputation and an unverified identity. I have to trust that he is real, but why should I?

This problem of identity has become even more elusive with the explosion of consumer AI software over the last year. AI is now able to learn and mimic outputs such as text, voice simulation, and audio tracks. AI video outputs have also become incredibly powerful within the last two weeks (February 2024) with the emergence of Sora by OpenAI. We are simply unable to verify what we see and hear without verifying the identity of the source(s) of the creators. This requirement of verifiable identity becomes imperative as our century closes in on its first 25 years.

2. Network Value

Citations have been used to establish value within information systems for as long as there have been writers. The concept of citing work to imply authority was part of the foundation for Google’s ranking algorithm, PageRank. As a greatly simplified example, the algorithm quantifies backlinks to webpages to calculate quality scores and rank each webpage on the Internet for its relevancy match to each user search query. This method remains valuable in soft and hard systems today.

Blockchain allows us to take this even further by valuing the verifiable human network of identities that engage with the work of writers, authors, and scholars who publish onchain information. The power of the network participants will give more weight to the hard reputation of the individual creating work, as well as the participants OF the network. Think along the lines of the often-promoted concept that you are the average of the five people you hang out with most often. Strong active peers would result in stronger network value and a stronger hard reputation score.

An easy example of this is when a famous art collector purchases the onchain work of any digital artist. By the famous collector joining the network of onchain collectors who had previously purchased the artist’s work, everyone gains value within the network from the hard reputation of the famous collector being present. The financial value of the work likely increases, but so too does the hard reputation of the network and its individuals. This is one of the strongest signals available, which is the financial commitment to a creator by a network. If a network is willing to fund a creator or information professional to create new works, then the work must have some explicit value potential.

Recall, that the factor which impacted my opinion of whether Gay and Oxman were plagiarists was the professional network response to the plagiarism accusations. Gay’s network did take issue with her work, whereas nobody attacked Oxman’s work. If we were to put these networks onchain, perhaps Gay’s supporters would still have come out in support of her, or perhaps not. The hard reputational risk, or opportunity, to support a peer within their onchain network would directly impact their own hard reputational score. Carol Swain came out swinging at Gay with her opinion piece on WSJ.com, and it seems as though she would have done the same if it were published onchain and directly impacted her own hard reputational score and those of network peers. That would be a strong signal that she believed she was adding value to the network by publishing her dissent onchain.

3. Productive History

Some might call this professional history or work history, but I’m framing this as productive history to include production outside CVs and professional resumes.

An example of this would be software developers writing lines of code that are pushed to production environments. Their work is quantifiable and may be assessed for quality using performance testing processes, bug reports, bug bounties, downtime, etc. This is a very effective system and would have wide application within the writing and creative professions. This is a job for AI, of course, and this will provide a great tool for the audience and industry professionals alike.

To make this example even more clear, let’s say two writers have written one million lines of editorial and our job is to establish the productive history for each. Each is clearly producing work, but is it productive and relevant? If one writer creates one million editorial lines with 500,000 lines that include factual errors, whereas the other writer produces one million lines without factual errors, we would likely consider the more precise writer to have a greater Productive History than the less precise writer. There are lots of nuances to consider of course, but the concept is the direction.

Claudine Gay appears to be guilty of plagiarism on some level in my opinion, but that doesn’t mean her work was not productive, nor should it prevent her from being productive in the future. A trustless system will provide Claudine Gay with a method to make a comeback in her career free from the constraints of a soft system that would experience public pressure to lean on her reputation as a plagiarist when making hiring decisions.

4. Expertise & Knowledge (Read-to-earn)

As with Productive History above, Expertise is a missed credential in our web2 and legacy world today.

Certainly, those who can afford the investment can benefit from the credential system of higher education to imply the minimum knowledge achieved as expressed by a university degree and one’s concentration of study, but this is only a very small part of the story. Those are the perishable credentials of a young person that don’t always accrete as a career progresses. One usually receives the biggest return on that investment simply from checking the box of hiring managers for roles that require a four-year degree within a specific domain.

One of the opportunities for contributors who publish onchain, or the audience that reads onchain information, is to publicly log information credits for the type of information they create, consume, or own.

An easy example here is for a person to quantify their reading or writing behaviors, such as with news articles or industry reports, books, blogs, informational videos, and the like. One will accumulate verifiable information credits for subject matters on which they spend their time. Should a journalist spend hundreds of hours familiarizing themselves with plagiarism, then he/she should forever be credited with having done the work to become an expert on plagiarism. Another person could perhaps have a degree in economics but read poetry in-depth, and they would become a verifiable source of poetry knowledge based upon their habits. In each example, the person who made an effort to accumulate knowledge around a subject would earn a hard reputation onchain as someone with experience on the given subject.

Most of us have exactly this opportunity to read or consume quite a bit of valuable information daily, but many of us submit to the temptation to simply scroll social media, or we fall down the path of low-value click-bait articles, thin media, or even corrupted information warfare. The incentive to choose a different path than the doom scroll behavior is weak, as there is little social or financial incentive present to change our behaviors. A read-to-earn incentive flips these decisions directly on their heads and/or obliterates the doom-scroll distractions entirely. Read-to-earn hard reputations would be similar to the developer who has written one million lines of flawless code, or the writer who has contributed one million editorial lines without being debunked by the crowds. Our consumption habits would be the hard reputations we deserve, and this could be great for many people. This type of hard reputation would be a boon for many knowledgeable but uncredentialed people worldwide.

Additionally, this idea of accounting for the knowledge density of a network is a very strong indicator of its peer merits. We often experience the vocal minority online which descends upon some subject and overtakes the conversation with significant noise and outrage but few meaningful contributions. These vocal minority movements are likely to include low network value peers with little domain expertise, but we are unable to discern between low-value contributions and some high-value contributions today without significant effort and distraction. This is a weakness of web2 commentary. We don’t know if contributions are coming from deeply knowledgeable individuals or crazed nuts looking to simply disrupt a conversation. Understanding the density of expertise of the network peers will provide additional signals to the people involved in conversations to assess the contributions of each person and their associated network value for the subject at hand.

A good but narrow example of expertise rankings from academics is the scholarly databases which provide H-Index rankings of academics and scholars. An H-index is a score that is calculated based on the publishing activities and influence of an individual that helps to determine their relative expertise among scholars. We are able to find information within Google Scholar for both Oxman and Gay, though their H-indexes were not calculated. The reported H-index for Oxman is 16, and for Gay the H-index is 10 or 11 depending upon the news report. What’s challenging about this type of index is it isn’t immediately available to the audience without significant effort, and it only includes work that is published through scholarly journals.

This same type of tool does not exist for journalists. We don’t have any indication of the expertise of Long, Newsham, Jones, Rufo, Cook, Swearingem, or even Peng as the CEO of Business Insider, nor Dopfner as CEO of Axel Spring SE, who himself is guilty of plagiarism for his academic work as noted above. Their backgrounds are all well grounded in academics, certainly, as all of them have received exclusive educations, and Peng is even a graduate of MIT. We don’t, however, have a mosaic of expertise beyond their degrees by which to fill in the context of perspective around this story and its subject matter. This is an elusive piece of the puzzle when we’re attempting to attribute reputation to the people writing these stories. Are they qualified? I couldn’t know from my research.

5. Opinion & Bias

We all live behind filters and within mental models we’ve developed to navigate the information of the world.

These are simple models we apply to reduce decision-making and information processing. It’s an evolutionary development, but it does saddle us with incorrect conclusions and potentially harmful behaviors at times. We develop opinions to manage a deluge of incomplete information, and we bias our actions toward decisions that feel safe to us at that moment. We are all wrapped in opinion and bias.

That being the case, we still have a responsibility to act with as little bias as possible and to gather as much information as is prudent to inform well-rounded decisions. Nowhere is this responsibility more important than when others are forming their own conclusions based on the information we serve to an audience as information professionals. The professional act is to deliver that information free from bias and be clear about opinion when opinion is promoted. We need to be upfront.

By acknowledging our biases and opinions for our audience, we should be able to help them frame the demonstration of our analysis as accurately as possible for their needs. If we are Democrat, Republican, or Independent, we should give that information up front in all transparency. If an information professional leans religious, then he/she should feel comfortable disclosing that specific attribute as part of the moral system used to bias personal decisions. These disclosures should not make us uncomfortable as information professionals. These explicit frameworks are easy to outline and should require little effort. This is common for financial disclosures, so it is not a completely new practice.

What is less well-known is what we unknowingly practice as information professionals. We may believe X but practice Y without being aware, and this is a good opportunity to use tooling to surface the unconscious frameworks we use to communicate information.

In our examples regarding Oxman and Gay, I would like to be aware of the biases and personal opinions of the journalists who wrote each article or contributed to the research. Christopher Rofu is very explicit in his writing. He intended to create a movement to remove Gay from her position. He was not hiding this bias. We may or may not agree with his intention, but he is clear, and this aids the audience and forces us to review the facts to make our own assessment of the evidence he has collected and published.

On the contrary, we know very little about the opinions and biases of the journalists who published the Oxman piece, at least not on the surface. With some digging and reviews of the previous work of the journalists, it does become clear which way their writing and editorial styles lean, but who would know without going down the rabbit hole? Certainly, all journalists will point to journalistic integrity and independence as the standard by which they pursue the craft, but that’s simply an umbrella of trust of the old trust me system. How should we verify their work holds true to that professional dictum?

The evidence suggests journalists should welcome the opportunity to disclose and make public their biases. As we see, Americans simply don’t trust the news and media professions today. That lack of trust is fixable in a trustless system where opinions and biases are known for each piece by each journalist within each publisher.

Online tools do exist at the brand level today and appear to provide a fair assessment of media brand bias and accuracy. The unfair result for the journalist, however, is we burden them with the bias of the brand under which they contribute. We can improve upon these tools on their behalf.

Three examples which provide some level of service at the brand level:

https://mediabiasfactcheck.com/about/

Deep resource with great methodologies

https://www.newsguardtech.com/

Pretty much unusable from its pay-to-play fee structure. Slippery slope to abuse. See Glassdoor as a web2 example of corporate branding tyranny.

https://www.allsides.com/media-bias/media-bias-chart

Of these three, I did find AllSides.com to be the most clear on its visual displays, as the following graphic shows below. The service, as mentioned above, is reporting on the brands themselves, not the actual contributing journalists. This is a web2 company using a pretty manual and clean method of indexing, but it isn’t scalable or real-time to expand within the landscape today.

Onchain ‘Hard’ Reputation and Trustless Systems Will Prevail

As of Q1 2024, the media landscape in America is actively imploding with zero sign of relief. The only natural result for the existing system is to continue its path toward complete centralization of the media in the hands of increasingly fewer ownership groups.

Fortunately, and very timely as it were, we have the opportunity to nurture the counterbalance by decentralizing journalism away from consolidated information intermediaries. The people will directly own the new information networks without corporate and government intermediation, and this new form of ownership will diverge from the 20th-century model of collective public ownership where public licenses were sold at auction by governments to the highest bidding corporation. Journalists and information professionals will be funded directly by the people in this new network. The journalists, educators, and enlightened media operators will rise from outside the centralized mainstream media system by building locally with the audience as owners.

As information becomes trustless and ownership becomes localized to the audience, many layers of expense and inefficiency will be eliminated. Information will become highly abundant within a trustless system as a result of these efficiencies, and it’s these efficient systems that will provide the opportunity to move the focus of audience capital toward funding new analysis and cultural advances. The journalist and scholar class will in turn have the opportunity to become more like a rabbi than a carnival barker, as the value of their work will be found within uniquely actionable information discovered while operating within the light.

The hard reputation of these information professionals is what will open this direct relationship with the community over time and help expunge the marks left behind during tours within untrusted media brands. The soft system judges and levies its debt in favors and trade leaving the once-maligned creators as servants to the mass media and machines of the state. The soft system imprisons the information class, whereas the hard system frees those who contribute value to the network.

Within a hard reputation system, Claudine Gay will have an opportunity to overcome her current reputation as a plagiarist. That label need not stick as a primary attribute in a hard reputation system, as we will be able to observe her own verifiable public index rising, or falling, over time as she works to add new value. While the H-index will provide some guidance for Gay’s scholarly work in the future, the real power for her reputation may come in making many smaller contributions more frequently and directly to the networked community onchain. Her contributions need not pass through the filter of the information intermediary of Harvard to have its highest impact. Indeed, this is obvious when considered objectively.

Similarly, journalists will have an opportunity to fix their efforts to contribute to network value and find the new communities in need of their unique and verifiable expertise. Thousands of new information networks will emerge from the news deserts to give voice to the untold stories that give rise to an informed and highly literate citizenry. The journalists will win the day over the corporate mass media to deliver upon the promise of the fourth estate in companionship with the people. Their vocation and position within the network will enforce the opening of a new era that will be built block by block onchain. A hard reputation will emerge from this work to be forever verifiable as one of an immutable type.

Thank You.

I hope my readers have found this post to be useful in understanding some part of the challenge we face in seeking to find the hard ground of truth in service of public discourse.

ImmutableType presents a method to explore how we may all work to solve our wide societal problems of conflict and continuous narrative grappling. Empathy is a short journey from understanding, and that hard ground of truth is what we will all stand upon to take this journey.

Thank you for reading. Please Like, Share, and Subscribe.

Damon Peters

Founder, ImmutableType

Further Reading

The below are many of the articles and published works used to inform my understanding of the information to create this post regarding the Oxman story and the background of Gay, Harvard, MIT, Axel Springer SE, KKR, Business Insider, and of course the journalists and management mentioned.

https://www.thecrimson.com/article/2024/1/8/lewis-reaping-what-we-taught/

https://www.semafor.com/article/01/07/2024/business-insiders-owners-clash-over-plagiarism-story

https://www.businessinsider.com/harvard-president-claudine-gay-to-resign-reports-2024-1

https://www.bostonglobe.com/2024/01/22/metro/mit-plagiarism-investigation/

https://www.bostonglobe.com/2024/01/08/metro/harvard-corporation-missteps/

https://www.bostonglobe.com/2024/01/08/metro/harvard-corporation-missteps/

https://www.businessinsider.com/bill-ackman-harvard-mit-president-resign-letter-2023-12

https://fortune.com/2024/01/04/bill-ackman-wife-plagiarism-doctoral-thesis-harvard-president/

https://fortune.com/2024/01/04/bill-ackman-wife-plagiarism-doctoral-thesis-harvard-president/

https://www.cnn.com/2024/01/04/business/bill-ackman-wife-plagiarism/index.html

https://freebeacon.com/campus/harvard-president-claudine-gay-hit-with-six-new-charges-of-plagiarism/

https://twitter.com/EmmaJanePettit/status/1742924745795067948

https://nypost.com/2023/12/22/news/plagiarism-harvard-cleared-claudine-gay-then-investigated/

https://nypost.com/2024/01/04/news/claudine-gay-plagiarism-scandal-questions-mount-for-harvard/

https://www.harvard.edu/blog/2023/12/12/statement-from-the-harvard-corporation-our-president/

https://www.axios.com/2019/09/14/joi-jeffrey-epstein-ties-mit-media-lab-professor

https://www.washingtonpost.com/style/2024/01/14/business-insider-oxman-ackman-axel-springer/

https://www.ft.com/content/72dbd392-14b8-4ec4-bce2-1c8dee0b250b

Dead link 404: https://gawker.com/tommy-craggs-and-max-read-are-resigning-from-gawker-1719002144

https://www.courthousenews.com/gawker-staffer-fights-hulk-hogan-subpoena/

https://www.wsj.com/business/media/axel-springer-business-insider-bill-ackman-neri-oxman-0c69d05a

https://www.thecrimson.com/article/2023/10/10/psc-statement-backlash/

https://www.wsj.com/business/media/axel-springer-business-insider-bill-ackman-neri-oxman-0c69d05a

https://www.nytimes.com/2024/01/06/business/claudine-gay-harvard-corporation-board.html

Why I Quit My Dream Job at MIT